People in Denmark are still receptive to getting vaccinated for COVID-19 – an update

Starting in late December 2020, people across Denmark began to receive vaccinations against COVID-19 with one of the four approved vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech; Moderna; Oxford/Astra Zeneca; Johnson & Johnson). According to the Danish Health Authority, the original aim was to vaccinate every adult Danish resident by the end of June 2021. However, the process has been slower than expected, and as of 17 June 2021, just half of the Danish population (49%) has received at least the first dose of the vaccine.

To learn more about Danes’ attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine, we have been asking 250 different people from the general population (age 18 and above) to fill out a questionnaire every two weeks since 10 September 2020. As of 17 June 2021, we have analysed questionnaire data from a total of 5,355 people.

What has happened since the vaccines were approved?

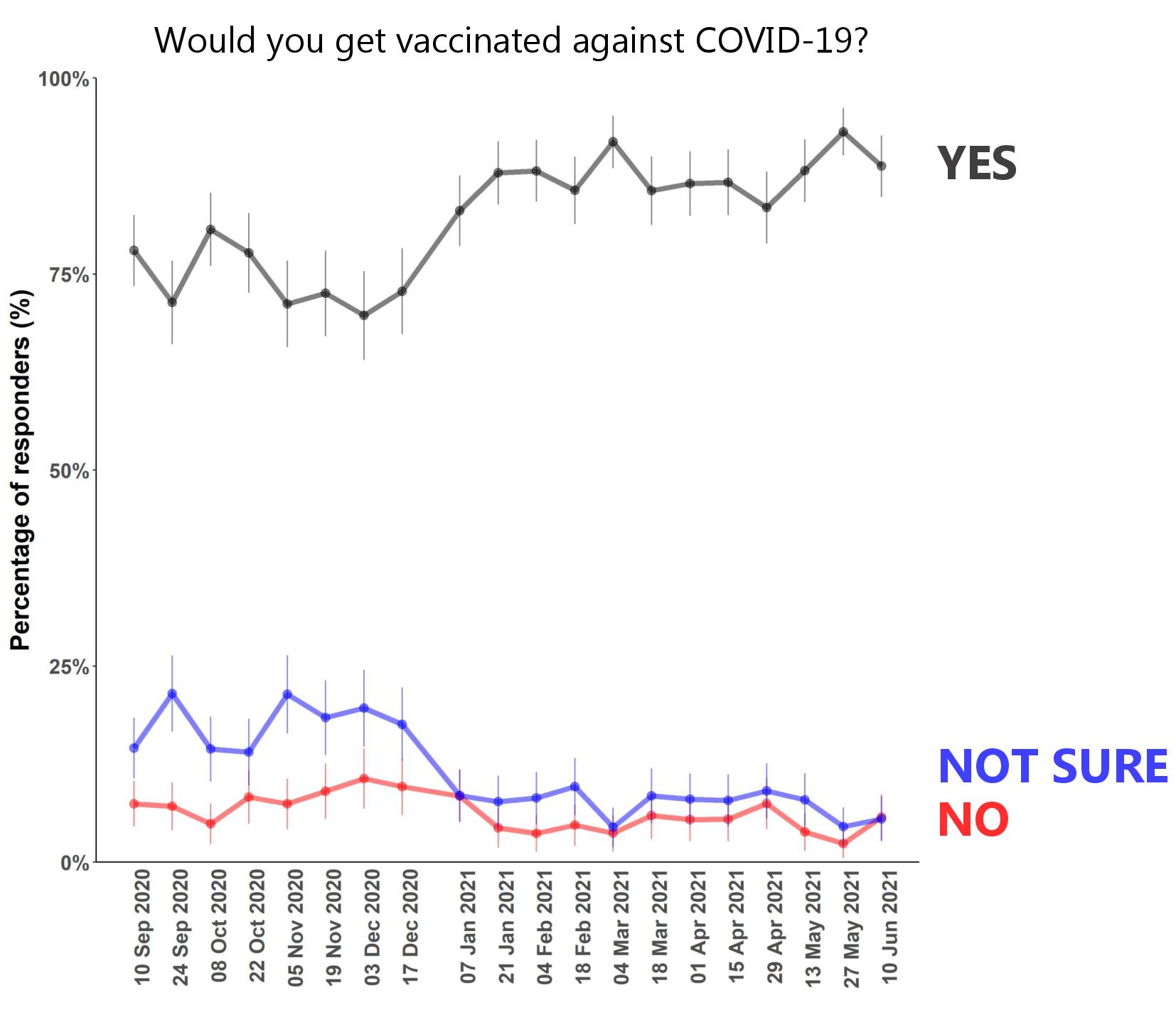

We reported our initial findings on Danish adults’ attitudes regarding a COVID-19 vaccine in early December 2020. At that time, 75% of the survey respondents said that they would get vaccinated, 18% were uncertain, and 7% indicated that they would not get vaccinated. We subsequently updated our results in February 2021 (when three vaccines were already approved); at this time, we observed an increased willingness to get vaccinated amongst the general population, with 88% of respondents stating that they would get vaccinated, 8% uncertain, and just 4% indicating that they would not get vaccinated.

Our current data analysis and the visualisation of time trends indicate relatively stable levels: since our February report and across all data-collection time points, between 83-96% of our respondents have indicated that they would get vaccinated, 4-10% are uncertain, and 2-6% will not get vaccinated.

Older people and those with a chronic illness are the most receptive to being vaccinated

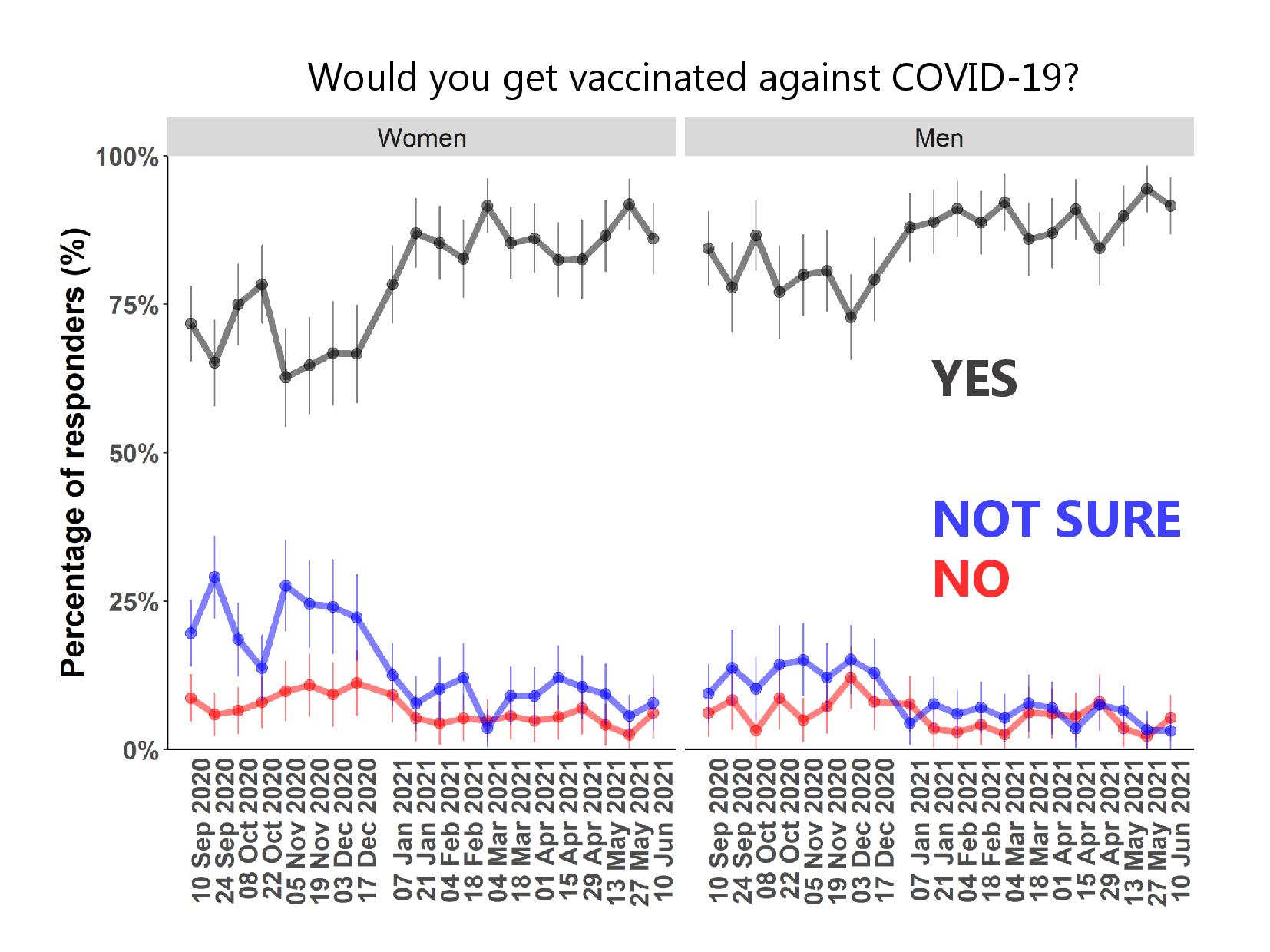

Since February 2021, we have not seen any differences in vaccination attitudes between women and men; both self-identified genders follow the average trajectories as reported above for the general population.

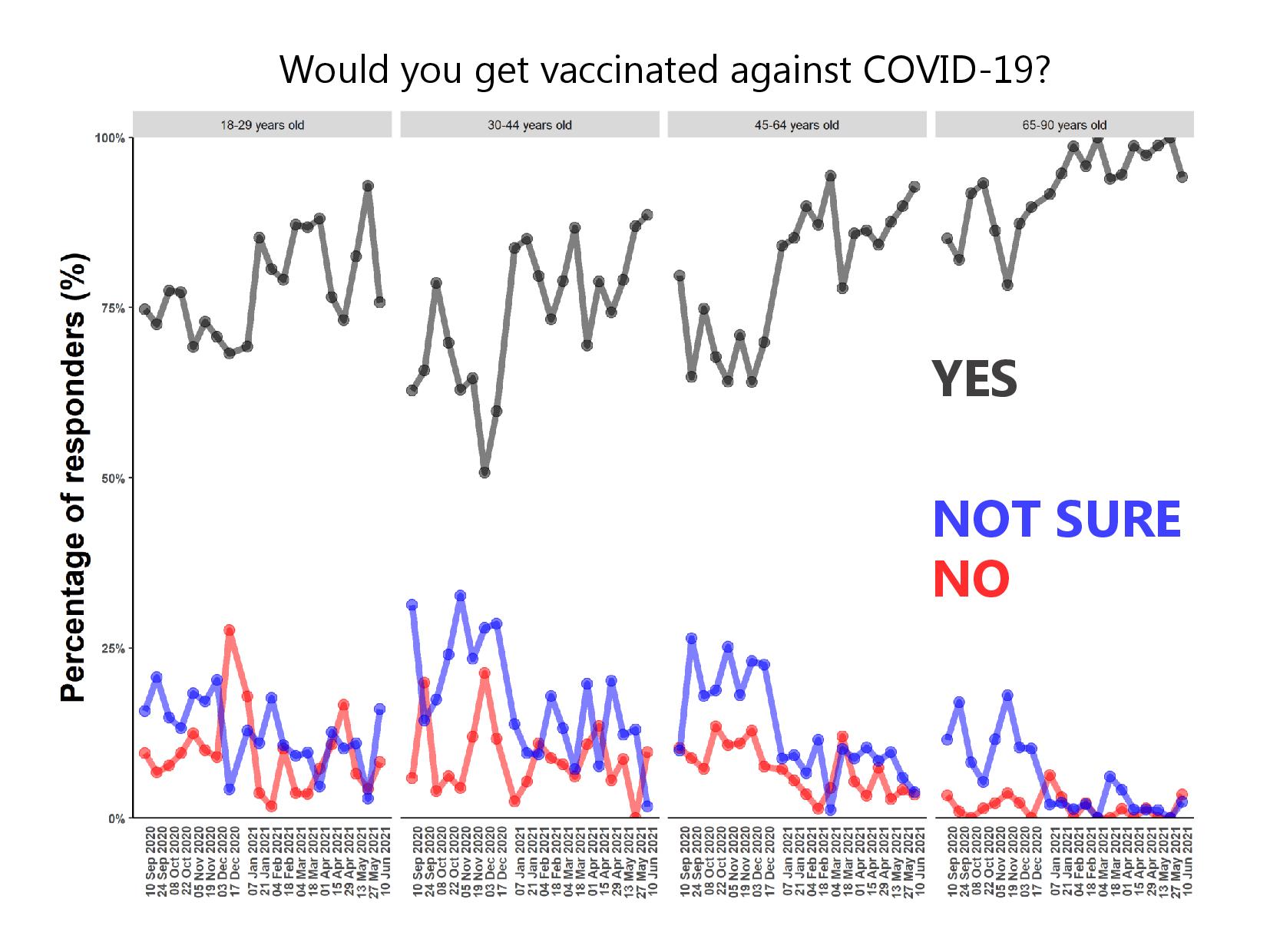

However, a different picture emerges when comparing different age groups in the population. Based on our data, there is a very high willingness to receive the vaccine amongst the oldest age group (65-90 years). Indeed, at any time point since January 2021, at least 94% and at times 100% of older people answered that they intend to be vaccinated or have already been vaccinated. The lowest willingness to be vaccinated is observed in the 30-44 age group, where at times only 70% reported that they plan to get the vaccine. However, based on the visualised percentages over time, we see an increased willingness to get the vaccine in all age groups, with fewer individuals reporting being uncertain.

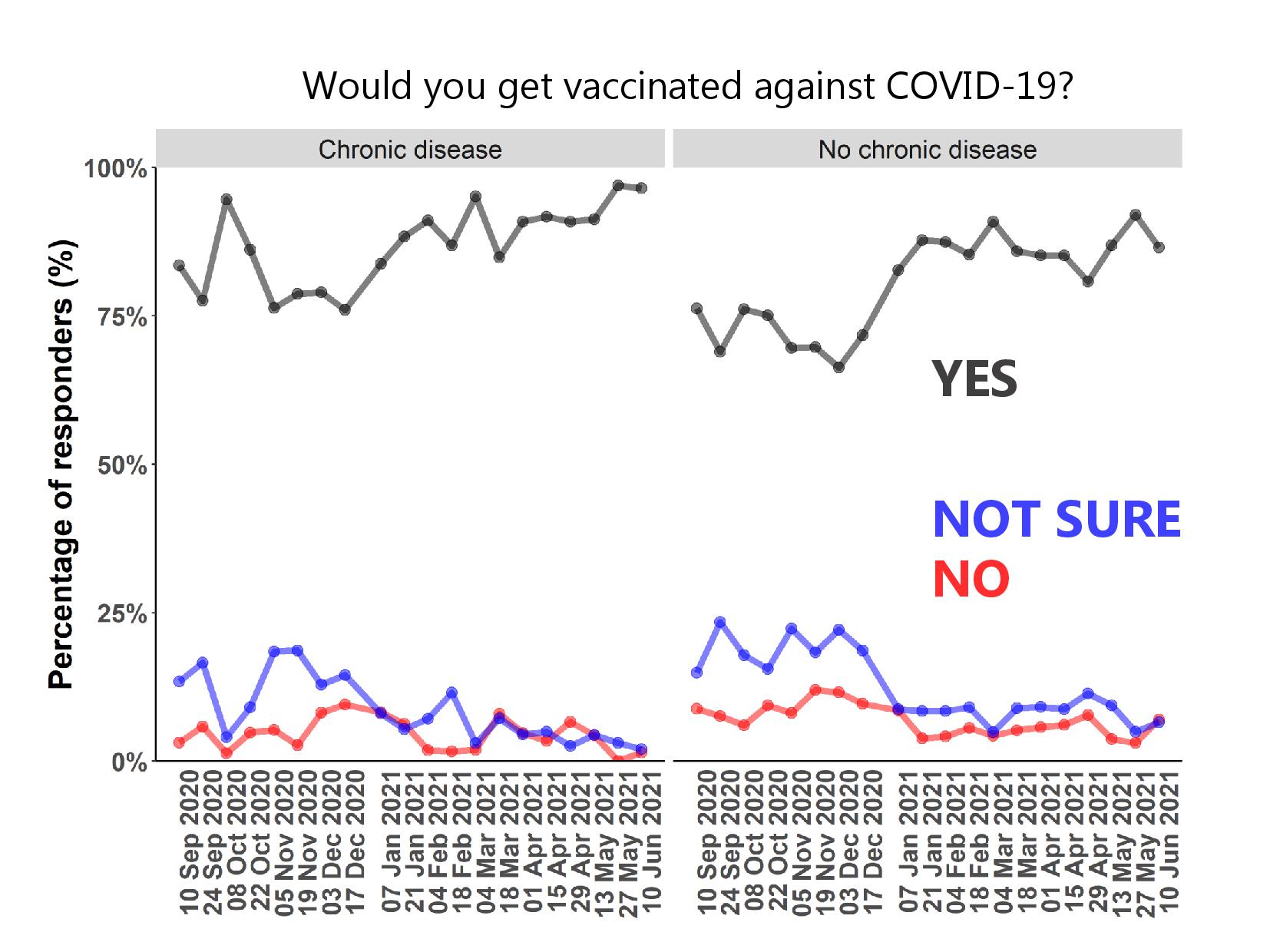

We also observe that those with a previously diagnosed chronic illness have a greater willingness to be vaccinated compared to those without such diagnoses. However, similar to the trends observed above, both groups show increasing trends in responding that they would get the vaccine, with fewer individuals reporting that they were uncertain over time.

Some people are still concerned about the vaccine

Since our data collection on vaccine attitudes started in September 2020, in total, 6% of our respondents have answered that they do not want to be vaccinated. In their responses to the questionnaire’s pre-defined options, the primary reasons given were that: a) they are concerned about possible side effects (62%); b) they do not consider themselves to be in a risk group for infection (35%); c) they are generally opposed to vaccines (22%); or d) they do not believe the vaccine will be effective (22%).

Between January and May 2021, the qualitative-research team supplemented their earlier round of interviews, which had only been conducted with respondents to the questionnaire. The new component consisted of interviews with 11 people who self-identified as critical of the government’s prohibitions (both protective measures and vaccines). For many of these informants, it is not vaccines in general that concern them but the COVID-19 vaccines in particular; they were sceptical primarily because the COVID-19 vaccines have been developed much faster than the typical timeline for vaccines. For example, Beate (age 24) said, “I just don’t think that it’s been tested enough. And then I just think, again, it’s strange – as if it [the pandemic] was all planned.”

Many of these interview participants emphasised that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) had only issued a conditional approval and were awaiting more follow-up data, which made them fear unknown side effects. Nicolai (age 43) said: ”It may make very good sense to urgently approve [the vaccines] and give them to the older part of the population – that is, the people who I said earlier we need to take care of, the vulnerable people. It just doesn’t make sense to give an urgent vaccine to people below, let’s say, age 50.”

Lisa (age 51) was critical of how the Danish health authorities have presented the vaccines as authorised: “I think that it’s wrong to write that it’s approved when the study design for the three COVID-19 vaccines doesn’t end until January, June, and December 2023, respectively.”

Opposition to the COVID-19 vaccinations is multifaceted and debates should remain open

Some of the interview participants also expressed concern about the new technology used in the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna (mRNA) vaccines. In particular, these people did not think that the risk associated with COVID-19 itself is greater than the risk associated with being vaccinated against the virus. Nicolai (age 43) said:

“I would like to have evidence before I get a jab for the sake of community spirit or solidarity (…) I’m not jumping on the bandwagon that I should get a vaccine for the sake of others. When I travel, I get a vaccine for my own sake, and that’s how it must be with my body. I mean, my body is my choice. And there are proportions with this disease, this virus – they are absolutely not anywhere near where you could say… where you could say, with a 0.20% mortality rate, then then it does not make sense to start demanding that we consider mandatory vaccinations and so on. It makes no sense because it’s not proportional here either.”

Scepticism about COVID-19 vaccines should be considered in a greater context in which some of the people who were interviewed believed the government’s prohibitions (both protective measures and vaccines) are not proportionate to the severity of COVID-19. They see an excessive use of force in the implemented restrictions – and they are unwilling to submit to this (state) power. Mikkel (age 39) emphasised the economic interests behind the vaccines, which he related to such power: “Think about how much money there is behind these vaccines. But it’s a kind of restructuring in which one tries to gain more power in order to control people”.

Sofie á Rogvi from the project’s qualitative-research team states:

While many of the people we interviewed welcome the fact that COVID-19 vaccines are now widely available, others are sceptical. In part due to the vaccines’ rapid development and distribution, these people consider the risks to be unclear and perceive the vaccines as potentially more dangerous than the SARS-CiV-2 virus itself. When planning the inclusion of more groups in the mass-vaccination programme – and possibly revaccinating people in the future – it is important that the Danish government and health authorities understand that those who oppose vaccines do not consider mass vaccination to be the only solution nor the best way to achieve herd immunity. Thus, if online and offline debates about vaccines and the management of the pandemic are dismissed or shut down by the government or media platforms – as these informants believe they have been – it may further increase some people’s distrust of both vaccines and the health authorities.