Housing conditions seemed to influence how young people coped with the initial lockdown in Denmark

The research project “Standing together – at a distance” has partnered with the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) to investigate how young people are experiencing and managing the ‘corona crisis’ in Denmark; i.e., the lockdown initiated to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants in the DNBC research project who had provided either their mobile number and/or private email address were invited to answer the DNBC-Corona online questionnaire between 30 March and 2 April 2020. A total of 53,323 individuals aged 16–24 were invited, and 13,002 answered the questionnaire within a week. These young people were subsequently invited to answer follow-up questionnaires each week until mid-May 2020.

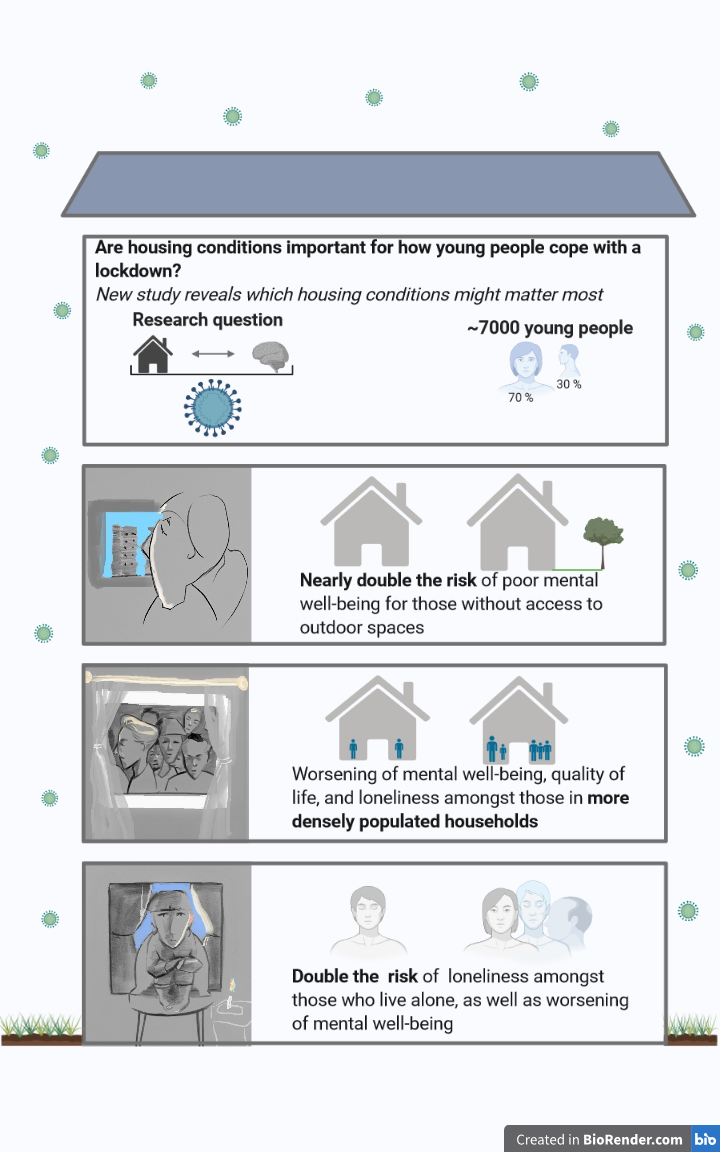

For the results presented here, our analyses focus on young people who had responded to the DNBC 18-year follow-up questionnaire between 2017 and February 2020 at age 18, and who subsequently responded to the DNBC-Corona questionnaire. Thus, 7,000 young people for whom we had data on housing conditions during the spring lockdown (i.e., March-May 2020) and mental health indicators before and during the lockdown were included. More than two-thirds of the participants were female and the average age was 20.

Certain housing conditions may predispose young people to poorer mental health outcomes

During the strictest phase of the lockdown, young people’s mental health appeared to be worse than before the lockdown; e.g., more individuals reported having low mental well-being during the lockdown (19%) compared to before (12%). Housing conditions are known to influence mental health under normal circumstances, but are likely to matter even more when populations are encouraged to ‘stay-at-home’. In this study, specific housing conditions seemed to influence how young people coped with the lockdown. The young people who seemed to cope the poorest were those living alone, those with limited space in their home, and those who had no direct access to outdoor space, such as a garden. The results indicate that young people without access to outdoor spaces had nearly twice the risk of having poor mental well-being compared to those with access. On each of the three indicators of mental health (i.e., well-being, quality of life, and loneliness), young people with less living space (i.e., square meters per person) seemed to cope more poorly. In addition, young people who live alone seemed to have more than double the risk of becoming lonely compared to those who were living with their parents.

Young people’s mental health may be protected by having access to outdoor spaces, enough living space, or living with others

These results provide insights into several tangible interventions that might protect young people’s mental health during future lockdowns. For example, if at all possible, young people should have access to and make use of outdoor spaces, avoid living in densely populated housing, and stay in the company of others.

Please note: The results reported in this post have not undergone peer-review, a process in which an academic journal invites other disciplinary experts to assess the quality of the research before publication. During this process, revisions may be requested, and a final accepted manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal may differ from one presented in more informal media. A detailed description of the study and all analyses performed are publicly available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.16.20245191v1